A perennial question about US politics is: Why is there no major working-class political party? An important reason is that working-class people have been intentionally discouraged from voting by election laws passed by the two major political parties that represent corporate elites.

Consequently, the major political parties have not had to appeal to working-class people to win elections. With neither major party speaking up for working-class people, they have had little reason to vote. A self-reinforcing cycle of disenfranchisement in law and politics has thus taken root. American workers vote in far lower proportion than any other democracy on Earth.

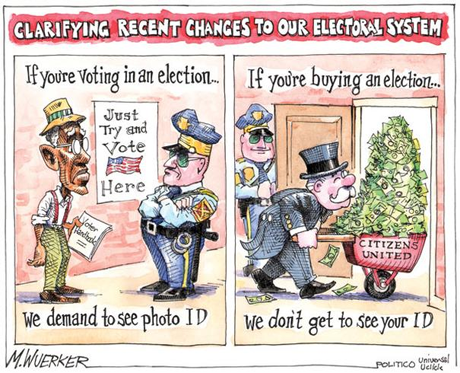

America is currently in the midst of a new wave of disenfranchisement. Since 2000, the number of states requiring voter ID has increased from 14 to 33. A 2013 Supreme Court decision struck down provisions of the 1965 Voting Rights Act that required pre-clearance by the federal government of changes to election laws in jurisdictions that had historically disenfranchised blacks and other people of color. In the wake of that decision, 17 states adopted laws requiring stricter voter ID requirements. Most of these laws require government-issued photo ID, which often requires a birth certificate to obtain. The time and cost of obtaining these documents discourages low-income people from registering to vote.

Republicans have been the driving force behind voter disenfranchisement laws. Although framed as a way to reduce voter fraud, the number of credible incidents of voting under false pretenses is only 31 out of over 1 billion votes cast since 2000. The clear intention of the Republicans is to reduce voting by people of color. Fifty years of white backlash politics by the Republicans have rendered the overwhelming vote of people of color against them. The Republican effort is a rearguard action attempting to maintain political office as the white electorate in the US declines in relation to the people of color electorate.

The federal courts have struck down these laws in Texas, Wisconsin and North Carolina in recent months because they violated the Voting Rights Act. A federal appeals court said the North Carolina law was passed “with almost surgical precision” to disenfranchise African Americans. The US Supreme Court let that ruling stand on September 1 this year.

The political and legal fight to resist and repeal voter disenfranchisement laws continues in the legislatures and the courts. The prospects for continued victories in the courts are good given the precedents of recent court decisions.

But that still leaves the problem that American election laws—before the recent slew of disenfranchisement laws—still create barriers that have kept the working class vote low for more than a century. The Democrats have shown little interest in eliminating these barriers. The post-New Deal Democratic coalition relies on a socially liberal but fiscally conservative message of equal opportunity in meritocratic competition for increasingly unequal results. But the meritocratic schooling, testing and other processes that sort people out are far from fair and equal, put working-class people at a disadvantage and reproduce the class structure across generations. The Democrats have chosen to rely on corporate funding and priorities and middle class votes, rather than a pro-working class program that would expand the electorate. In recent decades, Jesse Jackson and Bernie Sanders have campaigned as old-fashioned New Deal Democrats to expand the electorate with a pro-working class program. But the party remains firmly in the hands of the corporate New Democrats.

The current wave of disenfranchisement legislation is not the first time that political elites have attempted to reduce voting by working-class people. In response to the growing strength of the class-based biracial populist movement in the late 19th century and the socialist movement in the early 20th century, southern planter and northern business interests sponsored the passage of election laws that disenfranchised almost all black people and the poorer half of white people in the South and much of the immigrant working class in the North.

As the property qualification for voting was progressively eliminated in the antebellum period, the turnout of the voting age population for presidential elections rose steadily until it was consistently around 80 percent in the mid-to-late 19th century. After the passage of election laws that disenfranchised working class voters around the turn of the century, the turnout dropped steadily from 79 percent in 1896 to 49 percent in 1924. Since 1924, the presidential voter turnout has remained between 50 and 60 percent.

This first wave of disenfranchisement laws included literacy tests, poll taxes, immigrant disenfranchisement, and direct primaries that empowered candidate campaign organizations funded by the wealthy at the expense of party organizations that had organized and mobilized working class voters prior to the direct primary. But perhaps the most consequential change for the long run was the creation of voter registration requirements that required voters to take the initiative to register. Prior to voter-initiated registration, local governments were responsible for registering voters at the precinct level. Almost all democracies in the world make it the government’s responsibility to register voters. The uniquely American system of voter-initiated registration reduces the voter rolls considerably, particularly among working class people who tend to move more often and feel less engaged with politics that seem unresponsive to their concerns.

2012 data illustrates an under-registration problem that has persisted since the early 20th century. In 2012, 38 percent of the voting age population of 235 million was not registered to vote, representing 89 million people. 146 million were registered to vote, and 127 million voted. Turnout was 86 percent of registered voters, but only 54 percent of the voting age population. These figures show the crucial importance of voter registration to voter turnout. If people are registered to vote, they are very likely to vote.

So what is to be done about voter disenfranchisement in general and working class voter disenfranchisement in particular? Obviously, the fight against onerous voter ID laws must continue. Restoring the suffrage that resident immigrants tended to have in the 19th century would help. Ending criminal disenfranchisement would also help.

Universal Voter Registration would be the most important reform to include the working class in US elections. The historical data is clear: when people are registered to vote, they are likely to vote. The government should take responsibility for registering voters, which is the international norm.

In the end, however, only a mass-membership party of the left can solve the problem of working class alienation and voter abstention from the two-corporate-party political cartel. A mass-membership party where members are organized into active local chapters and support the party with membership dues can also overcome the problem of working-class voter demobilization caused by the party-disorganizing and wealth-empowering effects of the direct primary. The Socialist Party of America, which ran Eugene Debs as its perennial presidential candidate from 1900 to 1920, was able to maintain its membership party structure and elect hundreds of local, state, and federal officials by operating its party parallel to the primary system as it spread to most states in those years. It can be done again.