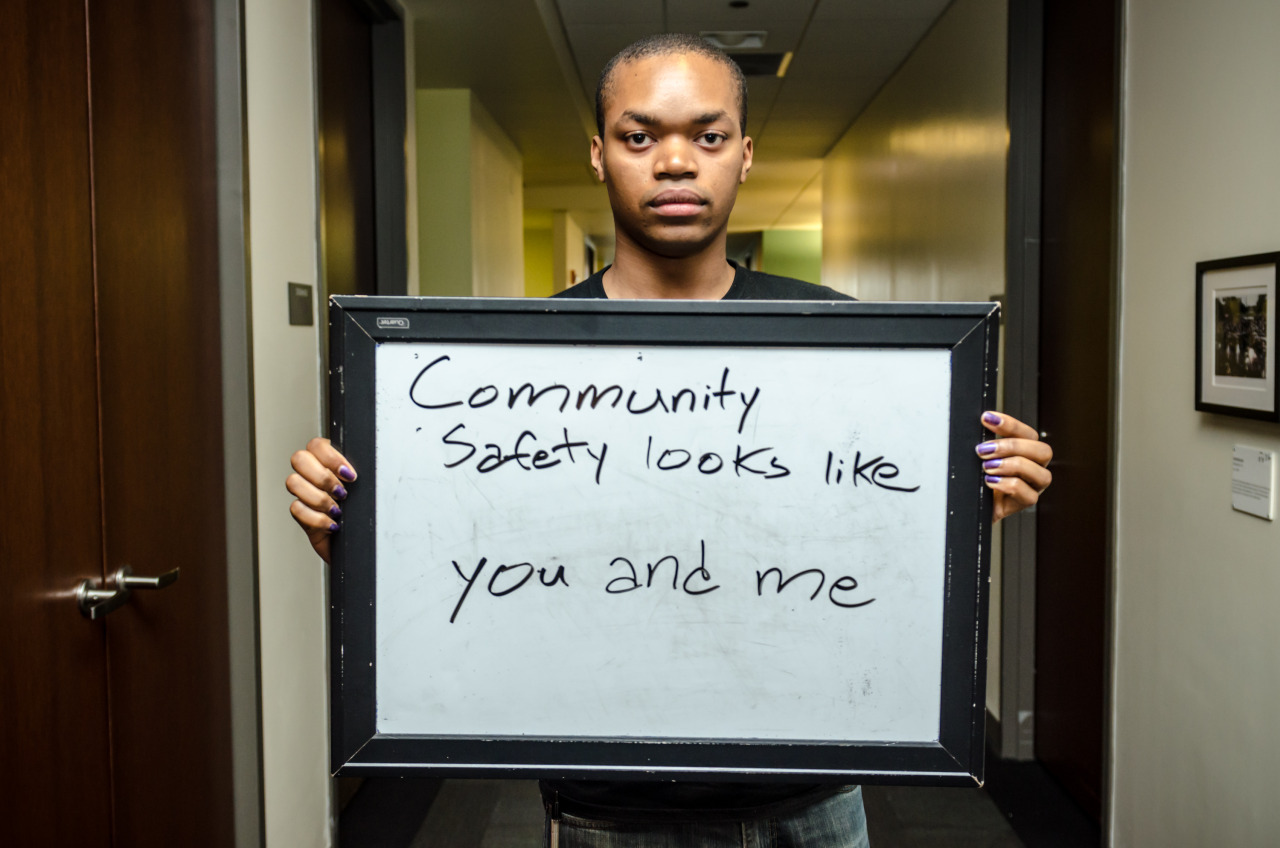

beyond policing. Photo: Sarah Jane Rhee.

Editor’s note: This is a reprint of an old article from Truhout.org originally printed in December 2014, but we found it to be currently relevant.

Looking for a New Years resolution? If you haven’t already, there’s never been a better time to resolve not to call the cops.

This resolution is more than a boycott or a political protest. It’s the beginning of a thought process and a dialogue, both internal and external, that challenges us to build new relationships with our friends, family and neighbors. It’s a spark in the imagination that leads us to dream about a free world.

For those of us who weren’t already aware, the events of 2014 made it clear that the police do more harm than good, especially in communities of color. From the streets of Ferguson, Missouri to Berkley and New York City, people from all walks of life have been loudly resisting the power of police who, all too often, prove themselves to be racist, armed and dangerous. At our rallies, we chant the names of the dead: Mike Brown, Tamir Rice, Eric Garner and countless others.

Some cops just bully people, but others kill, and the justice system lets them get away with it. In 2012, a study by the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement found that police summarily executed more than 313 black people—an average of one every 28 hours.

This is not a new problem. Police routinely target certain people—particularly people of color (especially men) and gender-nonconforming people—for minor crimes such as drug possession or loitering, or for no crime at all, simply stopping them for “driving while black” or “walking while woman.”

Last year, the American Civil Liberties Union found that blacks were 3.7 times more likely to be arrested for marijuana possession than whites, despite similar rates of drug use. In some counties, that number reaches 30 times higher.

As a result, people of color and other marginalized people are disproportionately warehoused in our vast prison system, which tears families apart and only exacerbates cycles of poverty, crime and violence.

Police officers are all individuals, and it’s impossible to say that they are all bad at their jobs. However, police have all sworn to uphold laws that systemically disenfranchise marginalized and working people for the benefit of the rich and powerful.

Consider Ferguson, where one young man participating in the protests in August told me that local police often harass and even ticket young black men for failing to walk on a sidewalk on a street that doesn’t even have sidewalks. If they can’t pay that ticket, the court fees add up, and they could end up in jail, separated from their families and livelihoods.

A few days later, the media began citing a report by local public defenders that detailed how racial profiling, along with a local legal system designed to keep people wrapped up in its web, fills the coffers of local municipalities in the St. Louis area that pay the wages of the cops who are supposed to protect and serve everyone equally.

This may not be news to you. Perhaps you have already resolved not to call the cops because you are unfairly criminalized by the color of your skin, your personal behavior or your gender presentation. You know from experience that the police are better at escalating than deescalating situations ranging from domestic conflicts to political protests and even the sale of a few loose cigarettes.

If you have not yet made this resolution, consider that not calling the police raises some difficult but important questions. It forces us to consider whom we feel potentially threatened by and why, and how we are defining “safety.” Do we feel unsafe in working-class neighborhoods, or around people with certain styles of dress or colors of skin? What prejudices ground this fear?

Resolving not to call the police inspires us to consider the alternatives. Instead of calling the police to complain about a loud party at your neighbor’s house, you could address your neighbors directly with the intent of having a constructive conversation about each other’s needs. Talking with our neighbors about taking responsibility for keeping our communities safe and happy helps us learn from each other and establish trust, the first steps toward building relationships that are strong enough to confront more complicated problems such as bullying or domestic violence.

Violence is the most serious challenge. If you feel that your safety is threatened, and the best option to avoid being harmed is calling the police, you should do it. Resolving not to call the police is not a rule, just a way to think outside the box. Rules are for the cops, not for us.

There are proven models for dealing with difficult social issues without the police. One example: Police in cities arrest more people on drug offenses than most other crimes, and a vast majority of all drug arrests are for possession, not sale or manufacturing. The harm reduction movement has effectively implemented many community-based strategies to reduce the harms caused by drug use while empowering drug users and non-drug users alike to work together toward healing and treating addiction.

Throwing people in jail for using drugs causes harm by seriously interrupting their lives, while reinforcing the stigma around drug use that drives people in need of help into the shadows. Harm reduction does the exact opposite.

Across the country and the world, people are using models of “transformative” and “restorative” justice to address offenses such violence, sexual assault and domestic abuse without involving the police. These models use cooperative processes, with survivors of the offense often directly involved, to repair the harm and trauma caused by the offense, while holding offenders accountable to survivors and working with them to transform their behavior.

Taking responsibility for keeping our communities safe and seeking justice under our own terms is not an easy task. It may sound radically ideal, like a dream. This dream, however, is already shared by a critical mass of people. It’s a dream of a world without police and prisons, a world where the struggle for true freedom is explicitly connected to our own collective empowerment and mutual compassion.

Keep this world in your heart. Dream beyond the police.

Note: Since the inception of the Black Lives Matter movement, there has been a rigorous national conversation about the role of the police as an institution. This is why the committee felt the need to share this older but still insightful piece. However, there are many other articles which we recommend to our readers on the broad topic of “origins of and alternatives to police.”

“We don’t need nicer cops, we need fewer cops” by Alex S. Vitale

“Alternatives to the police” by Evan Dent, Molly Korab, and Farid Rener

“Policing slaves since the 1,600’s” by Auandaru Nirhu

You can find these articles and many others at Mariame Kaba’s blog: http://www.usprisonculture.com/blog/2014/12/29/thinking-through-the-end-of-police.

—Aly Wane, on behalf of the PNL Committee