In November 2018, two female Muslims, for the first time ever, were elected to the US Congress: Rashida Tlaib (D-Michigan) and Ilhan Omar (D-Minnesota). Tlaib was born in Detroit and boasts Palestinian roots. Omar is an immigrant/refugee from Somalia, who also wears a traditional Islamic head covering (hijab). Given the ideals of religious diversity that define the United States—contrasted with the proportional lack of diversity in Congress—their elections are nothing less than historic, especially in

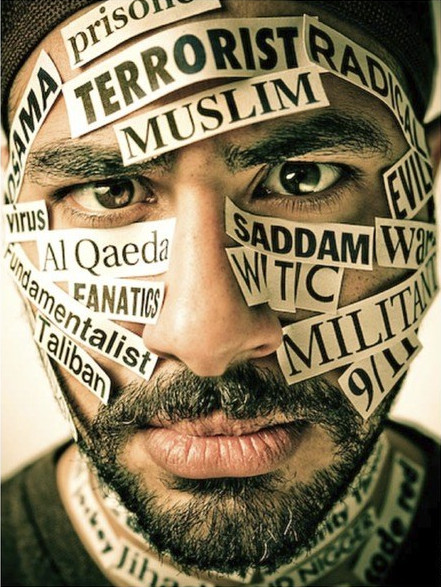

a post-9/11 Islamophobic world. Both women were sworn in on copies of the Qur’an. (Tlaib, incidentally, used Thomas Jefferson’s copy.) Notably, both have faced various degrees of Islamophobic backlash from fellow members of Congress, and I expect this backlash to continue.

As a college professor who regularly engages with students, media outlets, activists and other academics, their elections give me hope that a more public and visible marriage between government service and US Muslims will assuage some of the ignorance and fear that so many Americans hold toward Muslims. But at the same time, the current moment could also amplify Islamophobia. Certainly, there are no easy solutions to overcoming hate and ignorance, but baby steps are meaningful all the same. I’d like to now recount some of my own experiences with encountering Islamophobia and then offer some modest solutions that almost anyone can apply.

About a decade ago, I was flying out of the New Haven airport on my way back from a graduate student Islamic studies conference. While waiting for my plane to board, two unmarked FBI agents approached me, and asked me to follow them to a back room for questioning. I was taken aback, but I had been on a “random” security-screening list for the past two years whenever I flew, ever since I returned from Yemen on a US Department of State-sponsored scholarship to study Arabic (I never learned the specifics as to why I was placed on an airport security list). So, I wasn’t entirely surprised that these gentlemen wished to have a word with me about something.

The agents asked me about my business in New Haven as well as my trip to Yemen. “Why did you go to Yemen?” they asked me. “Because the government sent me there,” I replied. In a callous tone, one of the men replied back, “Oh, geez, you’d think they would have sent you somewhere less backwards.” I don’t think I engaged that particular comment, but I noted what was said and how it was said, and that it was coming from a government official. After boring the officers with details of graduate student life for a few more minutes, they finally let me on my way, but before I left, I asked why today was special: “What spurred you to approach me today, specifically, to ask me questions?” They said that the airport called them, and the agents alleged that they couldn’t be sure what the reason was, but offered, “Do you have any books about Islam or anything in your baggage?” I was traveling for an Islamic studies conference as a graduate student. Of course I had books about Islam in my luggage.

Even as a white guy whose native language is English, I have many more stories of first-hand accounts of Islamophobic behavior and rhetoric that have affected me directly. More troubling, I know a myriad of stories from friends and colleagues—many of whom don’t match my demographic description—and it’s often hard to know if things are getting better or not. Today, for example, we have a president who has said “Islam hates us.” And he supports banning Muslims, specifically, from entering the US. But, I also have the privilege of guiding students through the complexities and nuances of Islam and the lives of Muslims, and I watch people change their minds all the time because education can do that, so I remain optimistic.

Lots of polls suggest that most US citizens have never knowingly met a Muslim. Incidentally, although Muslims make up only about 2% of the US population, about 10% of US-based physicians are Muslims. So, lots of Americans have likely met Muslims in a medical context, and others, even if they aren’t aware. Also according to polls, unsurprisingly, people that have personal relationships with Muslims are more likely to hold positive views of Muslims more broadly. Why is it, then, that so many people who have never met Muslims have such strongly held negative opinions against people they know about, not from personal relationships, but instead from third-party

(both liberal and conservative) media? To paraphrase Islamic studies scholar Ingrid Mattson, media consumption is a public health crisis. Because I work with students, primarily in courses I teach about Islam, I think about Islamophobia often and encounter a range of informed, uninformed and misinformed points of view. My students routinely report, however, that the most impactful experiences that they have involve meeting Muslims, attending mosque services, and having sustained conversations with rooms full of diverse students who can constructively engage and challenge one another. By and large, my students regularly tell me that they enter our classes together with any number of biases but are able to move past them as they learn to humanize Muslims by taking in-depth looks at history, society, and intellectual debates. I also know that beyond the walls of the university, similar principles apply. My advice: Meet Muslims, learn about other cultures, and consume media with great caution. And assist your friends, family, neighbors and colleagues to do the same. Easier said than done, yet these things are within reach of the average person.

It is currently the month of Ramadan according to the Islamic calendar. This means that Muslims around the world, and in Syracuse, are fasting from food and water from dawn until sunset, as a spiritual practice designed to cultivate patience, gratitude and compassion. Later this month the 3rd annual Syracuse Ramadan Dinner will take place at Syracuse University in the Manley Field House. It’s free and open to the public, and you can register here: http://tinyurl.com/y39c7unt. Tell your friends. Come for the food. Come for community. People literally want to give you free delicious food, as a means to make the world a more peaceful and understanding place.

Elliott is an associate professor of religious studies

at Le Moyne College and also serves as co-chair

for the Study of Islam steering committee

in the American Academy of Religion.