Third parties thrive when the dominant political parties fail to provide solutions to social crises. Throughout US history, insurgent third parties have amplified demands for social change. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the Socialists and the Populist Party advocated for women’s suffrage, child labor laws and the notion of a 40-hour work week. The National Woman’s Party, formed in 1916, focused on the passage of the national suffrage amendment. Its militant members engaged in direct action at the White House and pressured mainstream politicians to make a national suffrage amendment a national priority until the Nineteenth Amendment passed in 1920. Republican President Abraham Lincoln was elected as a candidate of a third party. Up until 1854, there was no Republican Party. Its origins go back to the anti-slavery Liberty Party and the Free Soil Party. The dominant Democrat and Whig parties were both pro-slavery. By the 1860 election, slavery was the dominant issue facing the country, and Lincoln won with a plurality of the popular vote, 39.8%.

Those curious about the historic role of third parties in US politics and the obstacles we face should read Third Parties in America by Dr. Steven J. Rosenstone. Using data from presidential elections between 1840 and 1992, Rosenstone shows the importance of minor parties and independent candidates to social change movements, and outlines the legal and extralegal barriers to their participation and success.

Ballot access laws, which differ from state to state, are the first obstacle to third party candidates. In New York, a party’s candidate must receive 50,000 votes for Governor in order to be recognized by the Board of Elections. Once a party has ballot status, candidates can get on the ballot for the general election by collecting signatures from their party’s membership, typically about 5% of their party’s members in the district they seek to represent. Without ballot access, signature requirements vary by the office being sought. For offices that are voted on statewide—such as President and Governor—an independent nominating petition must be signed by at least fifteen thousand voters (read all about it in NYS Election Law Chapter 6-142).

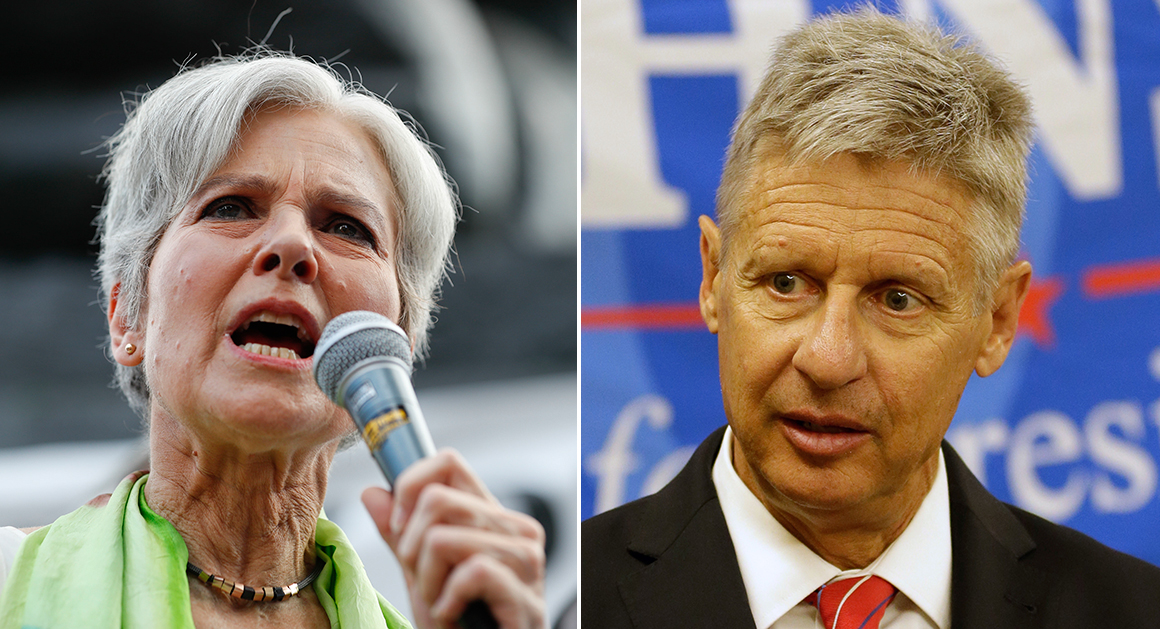

Another hurdle for third party candidates is access to debates. In the 2016 Presidential race, Green Party candidate Jill Stein and Libertarian candidate Gary Johnson will be on enough state ballots to win the electoral college votes necessary to be elected President. It’s not clear, however, whether they will be allowed to participate in televised debates alongside their major party opponents. The League of Women Voters (LWV) sponsored televised Presidential debates until 1984 when the Democratic and Republican national parties came together in a decision to move sponsorship of televised debates under their purview. The League challenged the move, arguing that this would deprive voters of the chance to see the candidates outside of their controlled campaign environment. In 1987, when the parties announced the creation of the Commission on Presidential Debates (CPD), the CPD invited the League to sponsor the last presidential debate of 1988, but placed so many rules on the possible format that the LWV refused to participate. In a press release, Nancy Neuman, then national LWV President, stated that the League had “no intention of becoming an accessory to the hoodwinking of the American public.”

In political science, Duverger’s Law holds that plurality-rule elections (such as first past the post) structured within single-member districts tend to favor a two-party system and that proportional representation tends to favor multipartism. So, while US founding documents don’t establish our political system as officially “a two party system,” electoral laws and regulations regarding the administration of elections contain significant structural challenges to third parties. Much has been written on the topic (I recommend Crashing the Party, the 2002 book by Ralph Nader detailing his experiences running in the 2000 US Presidential election. It is told chronologically, in the first person, and details many of the problems a third party encounters in a two-party system.)

Those who decide to cast a third party vote must endure the virulent criticism of those around them saying their vote is being wasted or worse. When Susan Sarandon spoke to MSNBC’s Chris Hayes and expressed that she might not be voting for Hillary Clinton in November, critics and Clinton supporters attacked Sarandon for her “privilege.” The attacks ignored the political points Sarandon raised—Clinton’s hawkish foreign policy, militarized policing, and the ruin of the working and middle classes by corporate greed—reasons she was a vocal Bernie Sanders supporter and opposed Clinton. For all the structural challenges facing third parties, perhaps the biggest challenge is breaking through voters’ perception of what is politically possible. In the 2016 election, the national success of the Green Presidential candidate will serve as a litmus test for the degree to which progressives in the US are ready to break up with the two party system and vote for candidates that advocate progressive policies, such as a foreign policy based on human rights, a public sector that guarantees human rights at home for everyone regardless of race or income, and solutions to the climate crisis.

On the 2016 ballot for President, a January 2016 Gallup poll found that nationally, Democratic and Republican party identification is approaching historical lows. According to Gallup’s finding, 42% of those surveyed identify as independents, 29% as Democrats and 26% as Republicans. Let that sink in. The political parties that dominate political institutions at every level of government across the US represent little over half of the population. With Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump proving to be history’s least liked Presidential candidates, 2016 looks like a promising year for third parties.

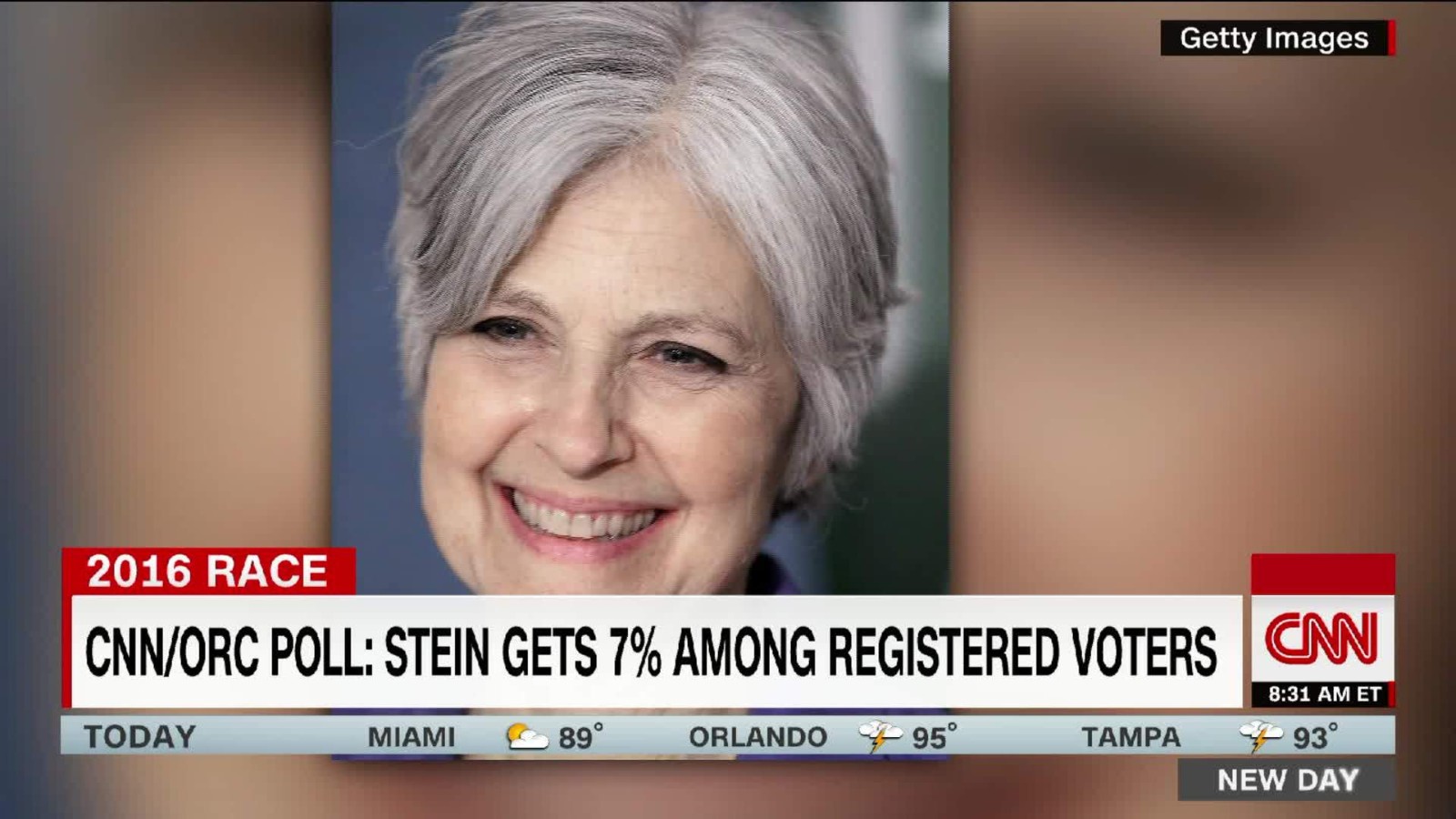

Like third parties of the past, the Green Party and its Presidential candidate Jill Stein are surging in popularity largely due to the failure of the corporate-funded parties to address the converging crises of our time—the climate crisis and the economic crisis. On the campaign trail Stein has been visiting the frontlines of the climate justice struggle. In August 2016, she visited Louisiana communities ravaged by the Louisiana flood (the August 11 storm dumped three times as much rain on Louisiana as Hurricane Katrina). Stein is the only national political candidate using her media platform to connect this extreme weather event to climate change. Juxtapose Stein’s Green New Deal agenda of climate jobs and ending fossil fuel extraction to the all-of-the-above energy policy of Hillary Clinton and the Obama administration. The rise in Stein’s popularity, particularly among young voters, should come as no surprise. Third party candidates, like Stein and the Green Party, aren’t in themselves movements. Rather, they offer yet another platform for movements to express our demands, influence public opinion, and force those who hold political power to respond.