Donald Trump brought his presidential campaign road show to Syracuse on April 16, 2016. I went to the OnCenter to see for myself what a Trump rally looked like. People wore T-shirts describing Hillary Clinton in misogynistic terms, exhorting Trump to “Build the Wall,” and to defend the Second Amendment. I saw people wearing regalia from the right-wing conspiracy site Infowars.com, which endorsed Trump and produced “Hillary for Prison” shirts and signs that appeared around the nation. The crowd was mostly white and male, but there were more women than I expected, and a few families.

When Trump finally appeared, the crowd was ecstatic. But as he spoke I struggled to keep track of his main points. Here was a man unaccustomed to speaking in complete sentences, much less a series of coherent ideas. The crowd didn’t care. He was their guy. They cheered as Trump demonized protesters, immigrants, Muslims and the media, blamed trade for the economic plight of rust belt towns like Syracuse, and promised that his unique deal-making magic could restore our lost prosperity. He was interrupted a few times by protesters shouting inside the hall, but Trump seemed to enjoy the opportunity for political theater. As he had done with Black Lives Matter activists at other rallies, Trump ridiculed the protesters and called for the heavy security presence to “Get ‘em out!” The crowd seemed energized by the silencing of perceived interlopers.

The next week in class, I talked to my students about the rally. One told me that she had also gone to the rally. Like me, she was there to observe, not to protest. But unlike me, she is a woman of color. She told me that she was harassed, that her presence was questioned by other attendees and that at one point she was hit on the head with one of the “Silent Majority stands with Trump” signs that the campaign staffers had distributed to the crowd. She wasn’t injured, but the incident was shameful and telling. Underlying the glitz and incoherence of the Trump extravaganza were undercurrents of intolerance for dissent, racial hostility and potential violence. Trump and a substantial proportion of his followers seem animated by a divisive politics of white nationalism.

White Nationalism

At the core of contemporary white nationalism are three closely related beliefs: (1) people’s political identity is based most fundamentally on their ascribed racial identity; (2) “America” as defined by white nationalists has been and should continue to be a nation based on white supremacy and European cultural traditions; and (3) white Americans are increasingly dispossessed of this birthright because of the political power of “the liberal establishment” and their allies among traditional racial minorities, along with their ideologies of cosmopolitan openness to the world, multiculturalism, and “political correctness.” Contemporary white nationalism depicts white Americans as both entitled to a secure position of superiority in this country, and victims of forces conspiring to deprive them of that birthright.

Author David Neiwert summarizes Trump’s racialized appeal by reference to “producerism,” a populist ideology that upholds “ordinary Americans” —hard-working, tax-paying, law-abiding—as pillars of the republic, beleaguered by liberals and their clients among the “undeserving” poor: “The ideology that is identifiable through [Trump’s] braggadocious and at times incoherent speaking style is the ‘producerist’ narrative, which pits ordinary white working people against both liberals—who are cast as an oppressive class of elites—aand the poor and immigrants, who are denigrated as parasites.” This form of populist political narrative lends itself to racialized interpretations in which the unproductive poor and burdensome immigrants are presumed to be people of color, dragging down “real Americans.”

Survey evidence indicates that persons with these kinds of beliefs were drawn to the Trump campaign from the outset. A Washington Post—ABC News poll from March 2016 asked whether “whites losing out because of preferences for Blacks and Hispanics” was a bigger problem in America today than “Blacks and Hispanics losing out because of preferences for whites.” While only a plurality of Ted Cruz supporters (37%) and Marco Rubio voters (35%) subscribed to this narrative of white dispossession, a clear majority of Trump supporters did (54%). Other researchers analyzed data from the January 2016 American National Election Survey using an index of multiple questions designed to measure indirectly whether respondents had high or low levels of racial resentment. They found that an overwhelming majority (81%) of white Trump supporters had high levels of racial resentment as measured by this index.

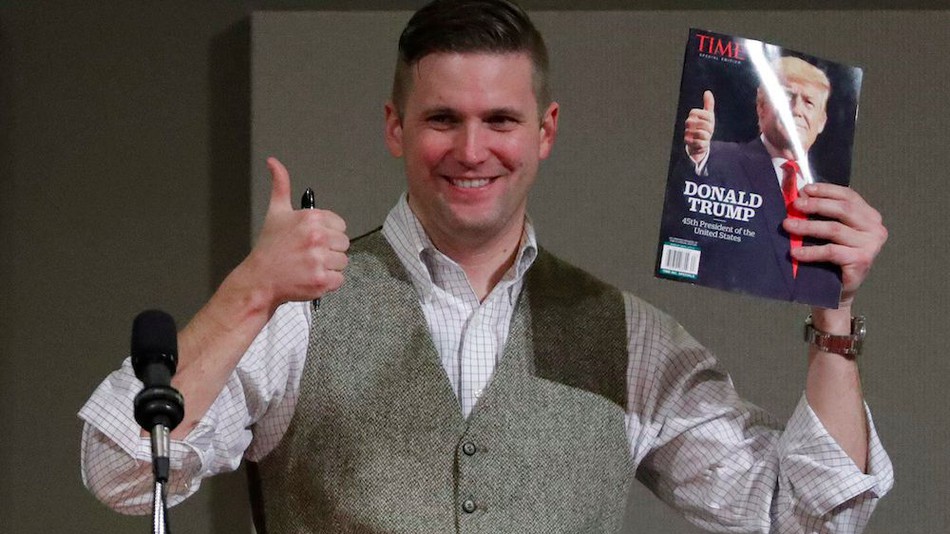

Klansmen, neo-nazis, and their fellow travelers in the Alt-Right—many of whom share a fear of demographic displacement they equate with “white genocide”—rode the Trump train. Leading White Nationalist Jared Taylor endorsed Trump because “he is not on his knees before Mexico and Mexican immigrants. Americans, real Americans, have been dreaming of a candidate who says the obvious, that illegal immigrants from Mexico are a low-rent bunch that includes rapists and murderers.” Andrew Anglin, editor of the neo-nazi Daily Stormer web site, framed Trump’s victory in terms of anti-Semitic conspiracy theories which are a staple of the racist right: “This was not a presidential election. It was a referendum on the international Jewish agenda. And the biggest part of that agenda is multiculturalism.” Richard Spencer, one of the leading figures of the Alt-Right, celebrated Trump’s election by shouting “Hail Trump, Hail our People, Hail Victory” while supporters in the audience threw up Nazi salutes.

Processes reshaping US society

To understand the context of this white nationalist resurgence, we need to take a step back from electoral politics and look at some longer-term processes that are reshaping this country. In the decades between World War II and the 1970s, real wages (corrected for inflation, so as to reflect the actual standard of living those wages can buy) for most US workers grew steadily. During these years, an unprecedented number of (mostly, but not exclusively, white and male) workers could gain access to the “American Dream” and the “middle class” standard of living that is associated with it. Many workers could reasonably expect their own prosperity to grow year-by-year, and for their children to enjoy even more material abundance than did their own generation.

Increasing affluence in exchange for hard work might then begin to seem to like a birthright. But for a complex set of reasons that I believe had mostly to do with a shifting balance of power between capital and labor, this “productivity bargain,” in which workers could expect greater output to be rewarded with greater income, came to an end. Since the 1970s, real wages have stagnated for most US workers. This, I think, lies at the root of what many Americans experience as a crisis of the American Dream, a birthright denied.

In recent decades, this economic malaise has coincided with a demographic transition that can be described as the browning of the country. Due to increases in immigration (especially from Latin America and Asia) and differential birth rates among various segments of the US population, white US citizens of European heritage are going to find themselves in a minority by mid-century. The confluence of these two processes, demographic and economic, has made it possible for white nationalists to depict the two as cause and effect. “Ordinary Americans” (implicitly white) are being deprived of their birthright by globalization, immigration, and increasingly assertive racial minorities who will soon make America their own, transform its European culture into something unrecognizable, and marginalize white Americans in “their own country.” This, I believe, is the dark fear that has driven much, if surely not all, support for the Presidency of Donald Trump.

White supremacy and racism have been part of American life since Columbus first set foot in the “new world.” In more recent times, social movements and political forces have been able to push back against it, delegitimize it, and limit some of its effects. But white supremacy remains an underlying element of our society. And sometimes it steps out of the shadows, openly claims that the nation belongs to white Americans, and attacks their perceived enemies. As Ian Haney-Lopez demonstrated in his important book, Dog Whistle Politics, since at least the 1960s the GOP has deliberately played to the anxieties of white voters with messages of racial backlash. The election of America’s first African-American president sharpened these fears of white racial dispossession and intensified the political backlash, paving the way for Trump’s overtly white nationalist politics. So while racism is nothing new, I believe the election of Donald Trump marks the culmination of a period of increasingly militant white nationalism in US politics.

Contradictions and Possibilities

Trump’s White House includes a number of advisers like Stephen Bannon—an ethno-cultural nationalist who sees Western Christian civilization as under threat of extinction due to global demographic trends and massive influxes of non-Christians and people of color. But Trump has had to broaden his coalition to include other GOP constituencies—business conservatives, traditionalists, and the religious right, each with its own priorities and demands. And Trump’s family also holds considerable sway in this White House. There are real tensions among these sectors, and it is far from clear whether Trump will be able to manage these contradictions. Meanwhile a massive nationwide wave of resistance has arisen to challenge the administration’s divisive politics and to articulate a more inclusive and democratic vision of what this country could be. The current situation, then, presents us with reasons for hope as well as profound concern.