The following stories come from veterans in the Syracuse Veterans’ Writing Group, held one Saturday a month in the Syracuse University Writing Center. The group focuses on non-fiction writing and is open to veterans of all ages and levels of experience. Anyone interested in joining the group can contact Eileen Schell at eeschell@syr.edu.

February 7

Robert Marcuson

February 7, 1968, I drove with my parents from San Jose to the Oakland Induction Center to catch a bus for Travis AFB to board a DC-something for the flight to Vietnam. With my parents standing beside me, I met my friend Danny MacKechnie, my training buddy in basic and Advanced Infantry Training and I met Danny’s mother. Of course you already know Danny dies in this story, else I would not be telling it. In November he tripped a hand grenade.

I was luckier. I was wounded early in April and sent home. Eventually, I ended up at Ft. Carson, Colorado, home of the 10th Mountain Division. In November I was summoned to the Commanding Officer. Mrs. MacKechnie had called my father to tell of her son’s death, and my father had called the CO. She wanted me to come to California, which I did.

Each day for three or four days, I drove an hour from my home to Concord, CA to sit and talk with a grieving woman whom I had met once waiting for a bus. We looked through her family photos, held hands, talked for hours about Danny—I had always called him Mac—talked about things I no longer remember. Family members milled about in the wings, taking in food when the doorbell rang, not interfering with us. The day of the funeral I stood alone at attention in my dress greens at the head of the coffin. They closed the lid and presented Mrs. MacKechnie with a folded flag as if in exchange for her son.

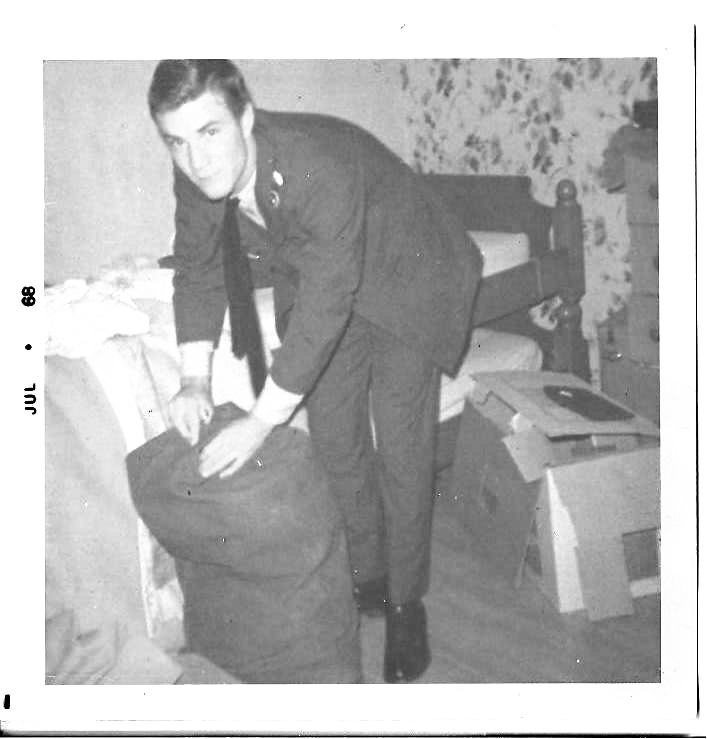

aunt snaps a last photo before

saying goodbye. The photo was taken

on February 7, 1968.

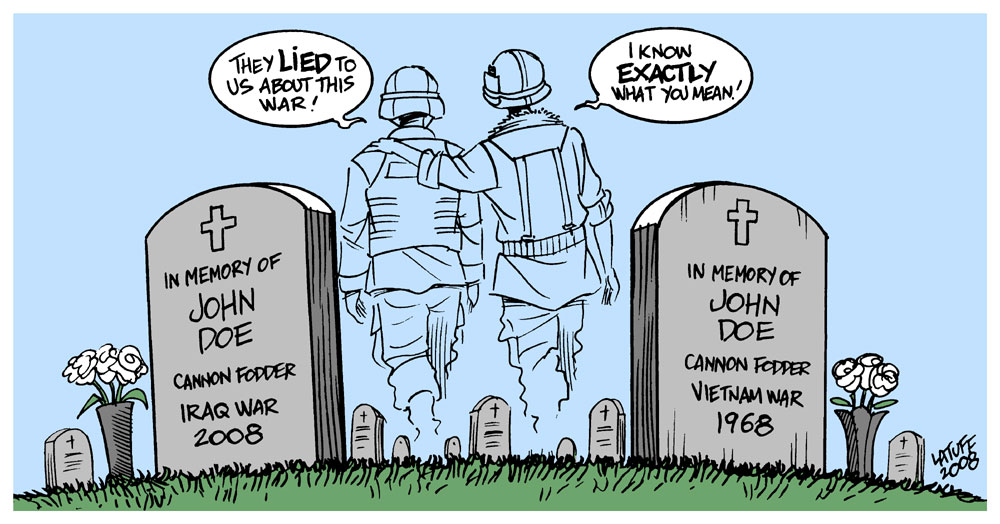

I had an insight in Vietnam. I realized—and I believe it was only hours or minutes before I was injured, that a person who easily picks sides in a war, any war, does not truly understand war. This may seem naive, but there are two ways to understand war. There is the war we build up in our collective imagination, the war we hear about from media and movies and in coffee shops, the war with all the justifications and rationalizations. And then there is the other one. These two versions of war do not mesh. I think there must be many veterans who suffer trying to reconcile what cannot be reconciled, what perhaps should not be reconciled. They want to live in the world generally as everybody else seems to. They want to accept and believe the common fantasy—that is after all practically the definition of being sane—but they cannot because they must fight with their own experience.

I don’t know. This is my speculation.

But I mention Mac’s—Danny’s— mother because we need to remember that for every mangled soldier there are damaged parents and siblings, friends and lovers. On both sides. And when I feel the urge to pick sides and root for one or the other, she reminds why I do not.

Robert arrived in Vietnam soon after the beginning of 1968’s Tet Offensive. He experienced Mekong Delta mud with the 3/60th Infantry, 9th Division, part of the Mobile Riverine Force.

————————————————————–

Hearts and Minds

Peter McShane

I dreamt of becoming a doctor before dropping out of college. I needed time off, but the draft loomed. Neither fighter nor patriot, I thought becoming a medic would improve my chances of admission to medical school. The best training was offered in Special Forces.

The first time someone died in my arms, it was one of our Cambodian mercenaries, Sann, a teenager who had known nothing in life but war. My kid brother’s age, he carried my medical kit bag and was unarmed. His father was one of our platoon leaders. I knew his mother from my dispensary. The family lived in our camp compound across the road. He was a good kid, would do anything for me. I’ll never forget the frightened look in his eyes. He cried: Bác sï! Bác sï! Bác sï! I tried to breathe life into his bullet-ridden body long after losing his pulse. Team sergeant told me to forget about him. “He’s a ‘Bode,” he said.

The first time I treated a Viet Cong soldier, it was another youngster. We found him cowering in jungle undergrowth after the chaos of a firefight. Stunned, he survived an artillery barrage with shrapnel wounds in his legs and a contusion on his forehead. He pleaded on his knees for me to spare his life. He supported his mother and younger sister, he said. His father and older brother were both dead. I bandaged his wounds, told him he was safe, and turned him over to the Cambodes. I didn’t realize they took no prisoners until after I heard the gunshots. Team sergeant told me not to waste my skills on the enemy.

The first time I saw mass casualties was nothing like I’d imagined. After the mortars and artillery, the rifle fire and the gunships, I could hear the screams of tortured souls pleading for mercy. Then we dropped napalm. The smell of burning flesh is like none other. Its slimy metallic taste lingers in the mouth for days. The kill zone was littered with diabolical shapes and heaps of ash. We suffered three dead and 13 wounded Cambodes. Six of them died on me. I could have saved them, but we only medevac’d Americans. And we had run out of supplies. Team sergeant said I’d get over it.

I almost lost an American during my last firefight. My CO took two bullets in the abdomen and one in the arm; I took one in the chest. Asï, my Cambode medic, helped me save the CO’s life and 15 of his Cambode brethren before I was medevac’d. Team sergeant said he was just getting to like me. “You’ll be ok.” Battlefield surgeons told me I was a lucky guy. The bullet missed my heart by a few millimeters.

I never became a doctor but spent the next 36 years running from memory fragments—faces of the dead, screams of the tortured, the stench of burning corpses. I abandoned my team, ignored infractions of the Geneva Convention, and failed our Cambodians. Guilty as charged, but I was alive.

The nervous breakdown came in 2005 after a reunion with my fellow medics. Their stories of suicide, drug abuse and broken lives consumed me. They were me…I was them. The VA shrinks told me I had post-traumatic stress disorder. I never would have admitted I had a problem. In and out of jobs, I filed for bankruptcy, and my wife walked out. I thought it was all part of the game of life. I trusted no one. I pushed friends and loved ones away. Angry and depressed, I couldn’t sleep, couldn’t work.

After Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Exposure Therapy, shrinks, counselors, therapists, and meds, I’ve begun to make sense of my life. Expressive writing helps me deal with my trauma.

I counsel vets from Iraq and Afghanistan. I see them suffer. I know the symptoms. It’s ok to ask for help, I tell them. The government owes you…you don’t owe them. But some just want to get on with their lives, leave the government behind, run like I did.

Not on my watch. I’m just getting to like them.

Pete served as a Green Beret medic in Vietnam from 1967-1968. He is finishing a memoir about his experience as a combat medic and his life afterward.

————————————————————–

The Piper of Al Asad

Derek Davey

During the hectic times of pre-deployment, the two corporals briefly crossed paths. One was an operator, a skilled, highly trained force reconnaissance Marine. His primary weapon was an M249 squad automatic weapon, a “SAW” in military vernacular. The other Marine was a supply man, a not so ostentatious duty, but a very valuable man. A warrior cannot operate without those who provide the necessary means of their trade. The two corporals were friends as one Marine to another are, mutually respectful of the other’s purpose and place in an infantry company.

The operator was a Scot and Irishman by heritage. His supply friend was very much a Scotsman and he was gaining skill as an accomplished bagpiper. He played his pipes in the evenings during the reserve drill days following secure from work. This both annoyed and delighted his fellow Marines depending on their individual taste for the music of the Highlands.

Supply was a busy place in the days before deployment to Iraq. After the SAW operator met the supply Marine for a new sling for his weapon, he paused in thought for a second and turned back to the supply shop. He found his friend again and asked, “Are you going to bring your pipes to Iraq?”

“Yes, I am,” the supply Marine said.

“Good,” said the operator. “If any of us gets hurt over there, I want you to play for him.”

The operator turned and walked away. The supply man stood and watched his friend for a few moments until he disappeared out of sight. They never spoke again.

Upon arrival at Al Asad, the sprawling base in western Iraq, the Force Recon operators found their billets and immediately went into training and planning for missions in the Euphrates valley. The supply Marines for the recon company joined a supply depot at a central command in Ramadi, ninety kilometers away. The two Marine friends were nearby, but in their travels they did not cross paths.

Two months after the recon unit arrived in Iraq, the supply Marine was summoned to the command office. “Marine, you are to get your butt over to the flight line ASAP. There is a helo turning, waiting for you.”

Not an out of the ordinary directive, the Marine had made other trips to Al Asad, but he had never heard that a helicopter was waiting for him. He turned to go gather what he might need and proceed to flight ops.

“And Marine,” The duty officer said firmly. “Bring your bagpipes.”

The flight to Al Asad was uneventful, but strange. The supply corporal was the only passenger. A Humvee was waiting for him at touchdown. The Marine driver said nothing to the corporal. He just sped to the recon company area.

The corporal stepped out of the vehicle when it came to a stop. He pulled out his pipes and his kit bag and immediately saw the reason for his summons. The company was in formation; the Marines in their platoons stood silently and sternly. A small lectern made of MRE boxes, sand bags and camouflage cloth was set to one side.

There was an upturned rifle with the bayonet spiked into the ground, a helmet perched on the rifle butt, dog tags swinging in the hot breeze. He noticed the neatly placed boots in front of the rifle, heels together, toes at 45 degrees. He then noticed the SAW resting on its tripod placed next to the memorial. The piper’s heart sank.

“Who was it?” he asked of a Marine standing nearby. He didn’t need an answer, nor did he hear one. He pulled himself erect, executed a left face and marched behind the formation to the far side.

Speeches were made by the fallen Marine’s closest friends including two who had also been wounded in the fire fight the previous Friday morning. Unabashed tears flowed as they told of the heroic stance of their fallen buddy, how he saved their lives. They spoke of his intense friendship, his support for his fellow Marines, on duty and off.

The formation came to attention. All saluted, were dismissed, and in single file walked past the raised helmet. They each stopped momentarily, touched the Kevlar, and spoke silently with sad eyes before they moved on.

The piper blew into his instrument and barked out the distinctive haunting notes of the bagpipe before gliding smoothly into melody:

Amazing Grace, how sweet the sound, that saved a wretch like me. I once was lost, but now am found; was blind, but now I see. Through many dangers, toils and snares I have already come…

The piper was finished and he turned back. He saw the Marine standing next to the same Humvee he arrived in. The supply corporal never knew who authorized the flight for him and his pipes. It didn’t matter.

Marines take care of their own.

Derek is a former Marine Corps Captain, a Naval Flight Officer. He served on active duty from December 1977 to May 1985. His son was a Marine Corporal, Force Reconnaissance who was KIA in Iraq on October 21, 2005. His memorial service as described is factual.

————————————————————–

A Veteran’s Perspective on Drone Warfare

Elliott Adams

I want to carry a banner at Hancock Airbase that says “drones are cowardly.” But a friend asked me, “Whether drones are cowardly is not your issue, is it? You want to abolish war. Isn’t the cowardliness of drones a distraction from your message?” But airmen believe in duty and honor even more than in morality or legality or Right, and drones are cowardly. They are a cowardly way for a soldier to participate in a battle field and they are a cowardly way for a President to project empire over little hapless nations and to not have to confront American mothers who lost a child.

If we can whittle away at the self confidence (or is it self delusion?) of the foot soldier, then that weakens the whole War Machine. After all, the reason I worked on the “Convergence to Resist Drones, Global War and Empire” is not just because I want to stop the despicable use of drones, but because drones are a way to talk about war: the illegality of all known wars, the stupidity of war, the stupidity of allowing the power holders to have a little war for themselves that we the people pay through the nose for and even send our kids to die in – not to mention killing the children of the hapless nation.

People do care. People came together to learn at the Convergence. People emptied their bank accounts to get others out of jail. I really think we may end war before I die.

Elliott, the former national president of Veterans for Peace, was an key organizer of April’s Convergence to Resist Drones, Global War and Empire. Elliott Adams is not a member of the Syracuse Veterans’ Writing Group.